Reflections on the 2024/25 Rainfall Season in Southern Africa to Date

By Tamuka Magadzire. 5 January 2025

Nail-Biting Uncertainty

Watching this season unfold has been a nail-biting experience—at least for me. Perhaps I need a thicker skin. After last season’s record-breaking drought, which featured a two-month-plus dry spell that decimated crops right when they should have been firming up their yields, it’s hard not to think, “Oh no, here we go again,” each time we encounter a dry spell. Is this recency bias? Or perhaps a fear ingrained by last season’s events? Either way, uncertainty seems to be a recurring theme this season.

From the “mystery of the missing La Niña”, to dynamical forecasts showing “equal chances” outcomes for many areas, this season has displayed higher than usual levels of uncertainty. A few weeks ago, I almost wanted to coin my own title: “Where is the ITCZ?” As the early dry spell extended, it really looked like the Intertropical Convergence Zone was running late to help establish Southern Africa’s rains. I need to consult a synoptic meteorologist about this! But fortunately it does look like things are getting back on track.

The issue of uncertainty was also central to my submission at the SARCOF meeting in August 2024. I emphasized the need for decision-makers to factor this uncertainty into their planning. I’ll elaborate on that in another blog post.

Possible Impacts of the Early Dry Spells

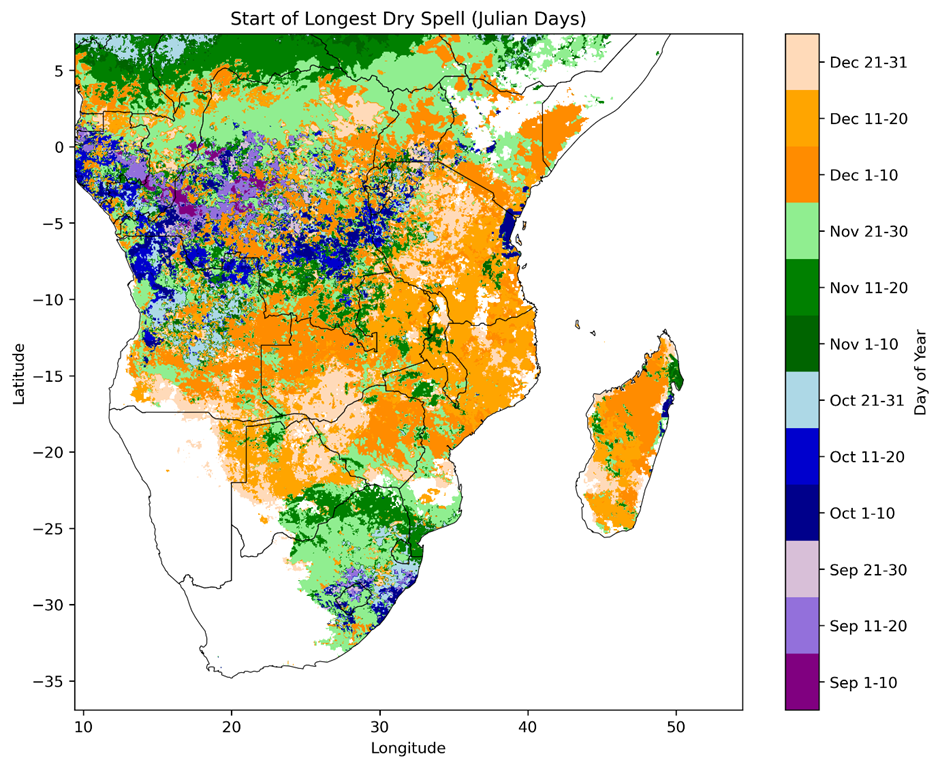

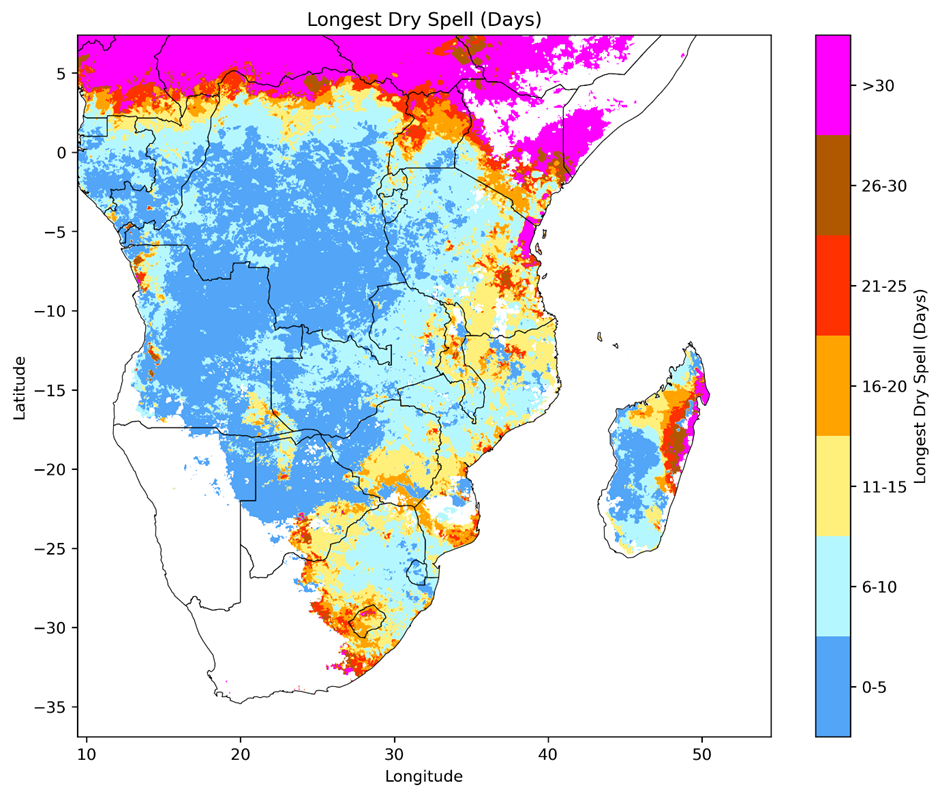

Following an October-to-November rainfall onset in many areas, central parts of the region experienced a dry spell that started early to mid-December (Figure 1). This dry spell lasted 11–15 days in areas like central Malawi, northern Mozambique, northern Madagascar, southern Tanzania, southern Mozambique, and southern Zimbabwe (Figure 2). Some areas, including parts of eastern Madagascar and southern Mozambique, saw even longer dry spells.

Figure 1. Start of the longest dry spell experienced between Sep-Dec 2024, after the onset of the rainfall season. I used definitions of onset and dry spell similar to those used by the Tanzania Meteorological Agency, namely (a) a 4 day period receiving at least 25 mm of rainfall and over at least 2 rain days and (b) a rain day having at least 1mm of rainfall. This is still an experimental product. The analysis was done using daily CHIRPS Prelim rainfall estimates produced by UCSB CHC.

Figure 2. Length of the longest dry spell experienced between Sep-Dec 2024, after the onset of the rainfall season. A dry day was defined as any day having at least 1mm of rainfall. This is still an experimental product. The analysis was done using CHIRPS Prelim produced by UCSB CHC.

The rains returned in mid-to-late December in many areas, but the question remains: was this in time to save crops planted earlier? Anecdotes suggest it depended to some extent on planting timing. A colleague monitoring the season told me that crops planted a few weeks before the dry spell largely survived, while those planted just days prior struggled to germinate under the intense heat. “It was almost like the seeds were being roasted in the ground!” he said.

Another farmer told me some of his neighbors, after their planted hybrid seeds failed to germinate in the dry spell, turned to him for grain from his previous harvest to replant, being unable to afford another purchase of improved seed. This highlights the critical timing of agricultural decisions and how closely they align with weather patterns—underscored by forecasts from Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe NMHSs, and ECMWF, which accurately predicted the hot, dry conditions.

The Rains Are Back

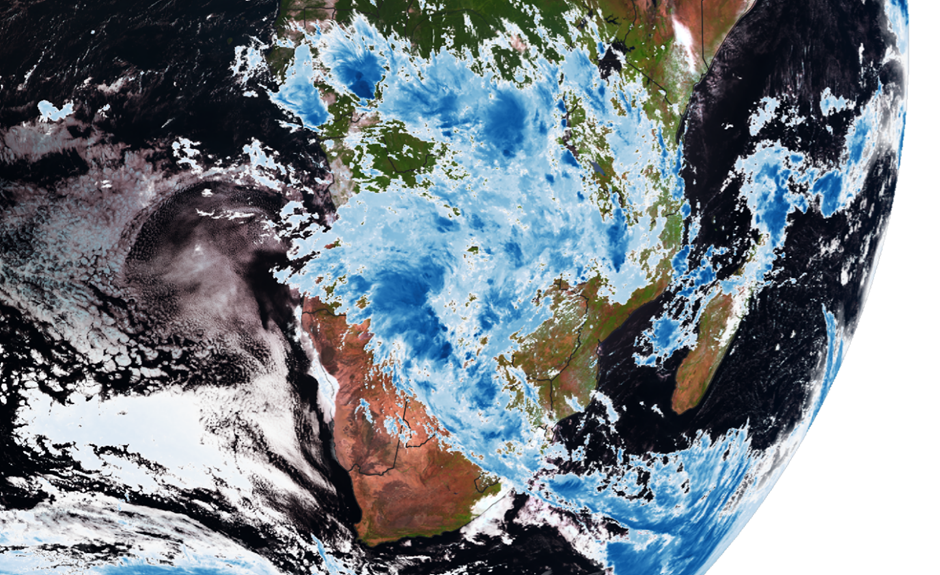

Recent Meteosat imagery confirmed the return of northwest-to-southeast cloud bands, also known as tropical temperate troughs (TTTs), bringing significant rains to parts of the region (Figure 3). For many, this has been a welcome relief. These cloud bands are one of the main systems that bring rain to southern Africa.

Figure 3. Meteosat MSG SEVIRI image for 1 January 2025, at 8:27am. Data source: EUMETSAT. The image shows the visible and near-infrared satellite image channels in the background, overlaid with a thermal infrared giving an indication of cloud top temperatures. The deeper blue clouds indicate colder cloud tops, which tend to be more likely associated with rainfall.

On a side note, it’s great to see that the Meteosat data is now freely available to researchers, the only requirement is to register on the Eumetsat data, figure out how to put together the download scripts, and start downloading and analyzing. This open access is a huge development and opportunity for research in meteorology – observations, modelling and forecasting, across Africa. Such open access will undoubtedly strengthen research across the continent.

Driving through southern Zimbabwe in late December, I witnessed some of the recent heavy rains firsthand.

Figure 4. Photos from a recent trip through southern Zimbabwe.

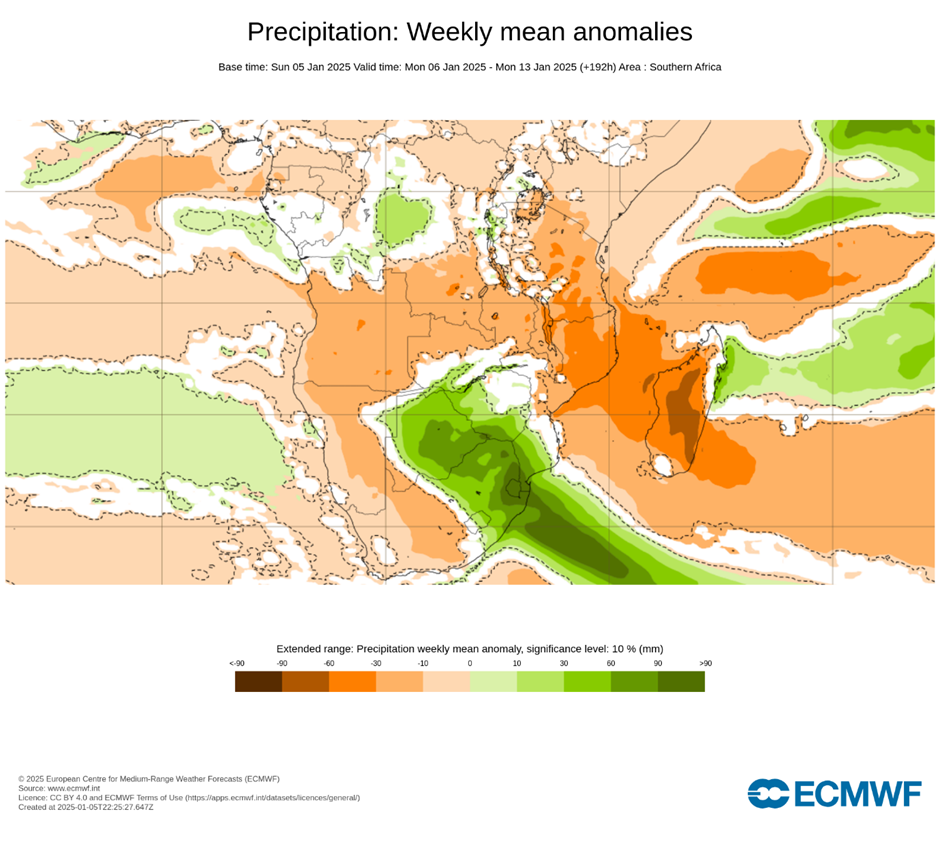

That said, conditions weren’t uniformly wet everywhere. Many areas had less rain than what I shared in the photos, but generally, evidence of wet conditions was widespread. Forecasts now predict continued rains in central parts of the region over the next week or two. The Zimbabwe Meteorological Services Department recently issued an advisory for heavy rains for the period covering 5-11 January 2025. The ECMWF forecast for the period 6-13 January suggest above normal rainfall for central and south-eastern parts of the region, while many other areas are forecast for below normal rainfall. (Figure 5).

Figure 5. ECMWF rainfall forecasts for 6-13 January 2025, issued on 5 January 2025. Orange areas show where rainfall is forecast to be below average, while green areas show where rainfall is forecast to be below average. In white areas, the models could not confidently determine whether rainfall would be above or below average. Image Source: ECMWF (CC BY 4.0). Downloaded and adapted from ECMWF Forecast Charts.

Looking Ahead: Opportunities and Risks

While many NMHSs forecast normal-to-above-normal rainfall for January–March 2025, they caution that these forecasts apply to seasonal totals over broad areas and don’t address the potential for dry spells, , which are common in many areas and season. Is now a good time to explore water harvesting techniques and store rainwater for future possible dry spells.

In my next post, I’ll share insights from Mrs. Botsanalo Coyne, a seasoned farmer in Botswana with an impressive water harvesting setup. It’s equally important to consider drainage options as some farmers face challenges with waterlogging during intense rains.

Join the Conversation

Are you a farmer, extension agent, agronomist, or other stakeholder? I’d love to hear your experiences and strategies for navigating these conditions. Share your thoughts in the comments below—what are your expectations for the coming weeks?

Your feedback is invaluable. Let me know your thoughts on this post and what topics you’d like to see in future SAWA blogs. Together, we can build a knowledge base to improve agricultural productivity and resilience across Southern Africa.

Local Language Support

I’m passionate about translating this information into local languages for broader community access. If you’re interested in translating this blog into your language, please get in touch!

Tamuka Magadzire