Early Rains, Early Dry Spells, and What Lies Ahead

By Tamuka Magadzire

1 December 2024

When Do the Rains Begin? A Look at Seasonal Onset

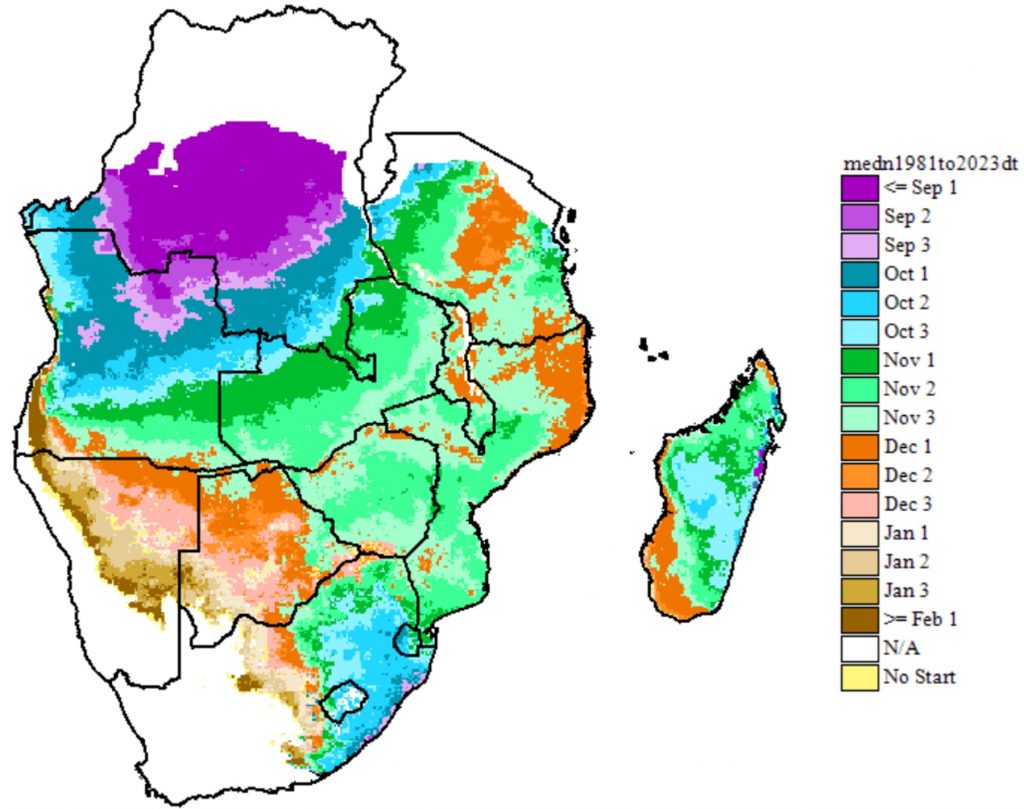

It is 1 December 2024, and a new summer rainfall season in southern Africa – well, almost new! Effective rains typically begin between September and December, depending on the specific location (See Figure 1). For instance, in parts of central Angola, northwestern DRC, eastern South Africa, Eswatini, and Lesotho, rains generally become effective in October. In contrast, areas such as Malawi, northern Mozambique, Botswana, and Namibia often see effective rains starting in December. For the majority of southern Africa, however, November is the usual starting point.

You may have noticed the term “effective start of rains” mentioned several times, but what does it actually mean? It refers to rainfall that occurs in sufficient amounts and over a sustained period to support successful planting, germination, and crop establishment – essentially, rain that is agriculturally meaningful.

Figure 1. Median start of rainfall season based on rainfall accounting. The median start of season is calculated using 1981/82 to 2023/24 CHIRPS satellite rainfall data. Source: FEWS NET, analysis done using GeoWRSI.

So far so good? Tracking the Early Rains

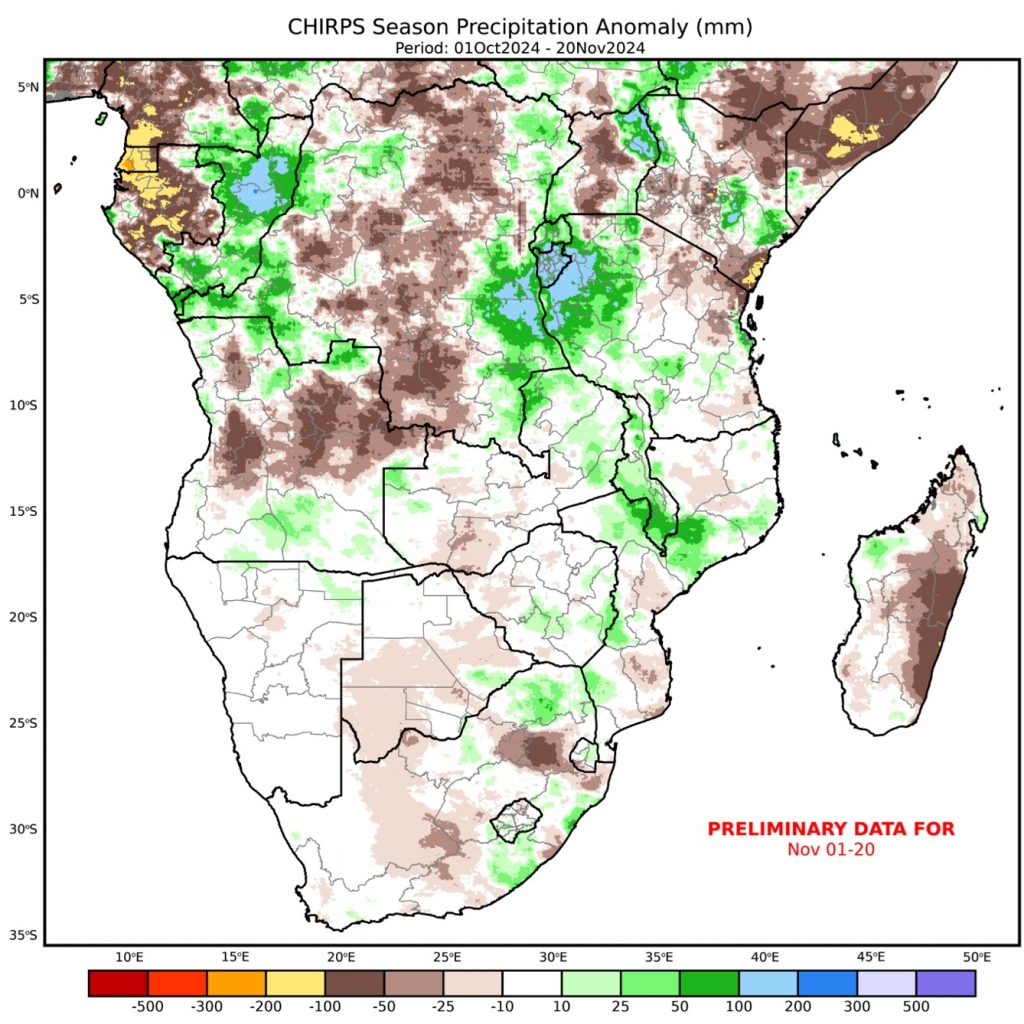

According to satellite rainfall data analysis by UCSB CHC, effective rains in most areas began close to their normal start dates, particularly in regions where rainfall typically begins by November. However, slight delays were observed in central Angola, eastern South Africa, and eastern Madagascar, which have also experienced below-average rainfall so far. Despite these localized delays, most areas have generally received rainfall conducive to crop growth.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of rainfall since October, highlighting areas with below-normal rainfall (brown), near-normal rainfall (white), and above-normal rainfall (green/blue).

Figure 2. CHIRPS Satellite Rainfall for 1 October to 20 November 2024 expressed as a difference from average. Yellow and brown areas show where rainfall has been below average over this period, while green and blue areas received above average rainfall. Source: UCSB CHC

An Early-Season Dry Spell: What’s Happening?

Rainfall generally started on time, allowing farmers to plant, generally on time. Rainfall has been near average or above average in many areas, promoting germination and crop establishment. That was the good news. However as we start the month of December, a number of forecasts have been issued predicting dry conditions for early December. In their recent weekly weather bulletin, the Zambia Meteorological Department released a forecast for rainfall below 25 mm, and “warm to hot” temperatures, in most parts of the country, for the period 30 November to 6 December. Similarly, the Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe (MSD-Z) issued a “Watch” indicating that “relatively dry and hot conditions” are expected over most of Zimbabwe for the period 30 November to 11 December. And in a press release issued on 1 December, Botswana’s Department of Meteorological Services warned of a heat wave expected from 2 to 6 December, with temperatures expected to rise as high as 41 degrees Celsius in some areas.

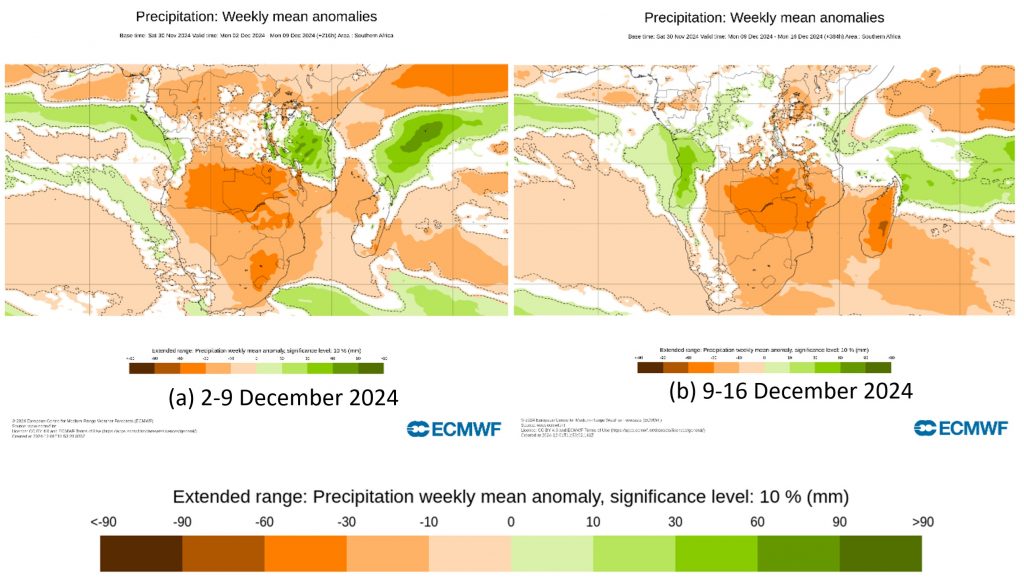

The latest rainfall and temperature forecasts from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) indicate that the warnings issued by Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe are part of a broader system, with below-average rainfall likely to persist for at least the next two weeks. Figure 3 highlights areas forecast to experience below-average rainfall, shown in orange.

It is important to note that forecasts become less reliable the further they project into the future. For instance, the forecast for 2–9 December in Figure 3 is more likely to be accurate than the forecast for 9–16 December. To address this inherent uncertainty, these 1-to-2 week forecasts are updated and refined daily, sometimes multiple times a day, ensuring that the most accurate information is available at any given moment. However, this also means forecasts can change significantly over time.

Additionally, the ECMWF forecast is based on a global-scale weather model, and while it provides valuable insights, it is not the only forecasting tool available. Different models and forecasts often provide varying perspectives, so consulting your National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS) for interpretation and localized context is always recommended. NMHS climate experts have experience working with multiple models and, through continuous use and validation, understand which models perform best under specific conditions.

The primary purpose of including the ECMWF forecast here is to illustrate the regional and widespread nature of the dry conditions flagged by forecasters in Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe, not to serve as a standalone advisory.

Figure 3. ECMWF rainfall forecasts for 2-16 December 2024, issued on 30 November 2024. Orange areas show where rainfall is forecast to be below average, while green areas show where rainfall is forecast to be below average. In white areas, the models could not confidently determine whether rainfall would be above or below average. Image Source: ECMWF (CC BY 4.0). Downloaded and adapted from ECMWF Forecast Charts.

The ECMWF temperature forecasts for the same period are predicting that air temperature will be above average in many of the areas where below average rainfall is being forecast. This typically happens – as conditions get drier during a summer dry spell, temperatures also get higher, because the cooling effect of water evaporating from surfaces and transpiring from plants disappears, as the surfaces, especially soils, get drier. Then the higher temperatures then cause more soil moisture and plant water to be lost due to evapotranspiration, and so a cycle ensues of increasingly hotter and drier conditions. This state typically persists until the rainfall returns, usually due to changes in the broader weather systems driving the dry spell.

Managing Early Dry Spells: Impacts, Strategies, and the Rising Heat Challenge

Given that some farmers had already planted with the October and November rains, the dry spell may raise concerns regarding its likely impact on the young crop. Cereal crops at an earlier stage of development tend to require less water, and so the impact of slight water deficits on yields is generally less severe than when the crop is at a more advanced stage of maturity. On the other hand, insufficient soil moisture soon after planting and during the germination stage can cause some seeds to fail to germinate fully, or lead to weak and uneven germination. This could then result in poor crop establishment, and uneven plant stands, which typically ultimately affect crop yields

The prevailing situation highlights the importance of understanding how early-season dry spells can affect crops. Prior work, particularly in the area of conservation agriculture, suggests that various measures can help improve the outcomes during dry periods. One such measure is supplemental irrigation, which Nangia et al [1]. define as “the addition of limited amounts of water to essentially rainfed crops to improve and stabilize yields when rainfall fails to provide sufficient moisture for normal plant growth”, and was shown to consistently improve wheat yields in one study when applied at time of sowing [2]. This underscores the critical need to increase the adoption of water harvesting and expand operational irrigation facilities. Similarly, mulching has also been shown as an effective way of conserving soil moisture and thereby increasing the water available to crops during dry spells [3], particularly after germination of the crop, as mulching suppresses germination of plants including weeds. Weeding with minimal soil disturbance protects crops by reducing weed pressure and competition for scarce soil moisture during dry periods. In cases where germination is poor, farmers may be forced to gap-fill or undertake outright replanting where necessary, resources permitting. In many areas, the planting window remains open, with opportunities for planting extending into December and, in some cases, even January

With the rising temperatures already occurring under climate change, the impact of heat stress on animal and human health has become an additional concern. Prolonged exposure to heat can lead to dehydration, heat exhaustion or heat stroke, particularly among vulnerable groups, and especially outdoor workers such as agriculture labourers engaged in physically demanding work. In their Watch for the period 30 November to 11 December, MSD-Z emphasized the importance of staying hydrated and protecting oneself from direct sunshine during this hot, dry period. Livestock are also highly susceptible to heat stress, which can lead to reduced productivity, fertility challenges, and heightened vulnerability to diseases. Ensuring sufficient water availability for livestock during hot periods is crucial for maintaining their health and mitigating potential losses in agricultural productivity. This is not an exhaustive or authoritative list of interventions to implement during a dry spell, nor is it intended as an advisory. Farming decisions are highly situation-specific and should be made with careful consideration of current and forecasted conditions, in close consultation with relevant experts such as agricultural extension officers or agronomists. It is also essential to regularly access continually updated forecasts, and rely on authoritative forecasts from official sources, such as the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS), to inform these decisions.

Seasonal Outlook: Navigating Early Dry Spells with Hope for Better Rains Ahead

The seasonal forecasts for the 2024/25 season issued by the SADC Climate Services Centre (CSC), as well as by national meteorological agencies, indicated expectations of normal above normal rainfall in many areas , offering hope for good overall rains. However, the climate forecasters from these agencies also highlighted that first half of the season, October-to-December 2024, could be drier than usual, with a forecast of normal to below-normal in many areas. In contrast, a more optimistic forecast of normal to above-normal rainfall was more prevalent in the second half of the season. The current/forecast dry spell being experienced is, therefore, somewhat consistent with the forecast for normal to below-normal rainfall in the earlier part of the season, in many areas (although, admittedly, at different time scales). Successfully navigating and managing these early dry conditions could position farmers to take advantage of potentially more favorable weather in the second half of the season, assuming the forecast for normal to above-normal rainfall for January-to-March 2025 is realized.

What are your thoughts? Join the Conversation

Are you a farmer, an extension agent, an agronomist, or another stakeholder? I would love to hear your experiences and thoughts on this topic in the comments section below. What are your expectations given the forecasted dry spell? What strategies or actions are you planning to implement to navigate these dry conditions? If you are a forecaster or an expert in indigenous knowledge systems, I’m curious to know your perspectives and insights.

Thank you for taking the time to read through this post to the very end! Your feedback is invaluable – let me know your thoughts on this topic in the comments, and feel free to share what topics you would like to see addressed in future SAWA blog articles. Let’s keep the conversation going on agrometeorology issues in southern Africa. Together, we can share knowledge on how weather impacts agriculture and contribute to a collective knowledge base that helps improve agricultural productivity and farming practices across the region.

Local Language Support

I am passionate about getting this type of information into local languages for easier consumption by communities. If you would like to translate this blog post into your local language, please get in touch here

Further reading

[1] Nangia, V., Oweis, T.Y., Kemeze, F.H. and Schnetzer, J., 2018. Supplemental irrigation: A promising climate-smart practice for dryland agriculture.

[2] Ilbeyi, A., Ustun, H., Oweis, T., Pala, M. and Benli, B., 2006. Wheat water productivity and yield in a cool highland environment: Effect of early sowing with supplemental irrigation. Agricultural Water Management, 82(3), pp.399-410.

[3] El-Beltagi, H.S., Basit, A., Mohamed, H.I., Ali, I., Ullah, S., Kamel, E.A., Shalaby, T.A., Ramadan, K.M., Alkhateeb, A.A. and Ghazzawy, H.S., 2022. Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy, 12(8), p.1881.

Tamuka Magadzire